Beta-Zero (Alpha) - Can AI set climbs?

I built an AI climb generator for my home-wall using sequential neural networks, a custom React UI, and aggressive data augmentation.

What’s up y’all! It’s Evan McCormick, professional adult at large, and I’m snowed in at my humble backwater home in upstate New York. Now, I’m normally a pretty active individual, and I’ve spent the last 4 winter seasons skiing as much as possible, but my current financial and locational situation bars me from the mountains for the time being. The one thing keeping the cabin fever at bay is…

My home climbing wall, “The Sideways Wall”

I built this wall over the summer, and since then I’ve set over 70 climbs on it, in my own unique style. But there were not enough climbs. So I begged my friends to couch-set some climbs for me (This dope drop-knee is from my friend Nick), and in return I would send them.

But there were not enough climbs.

So I went global, setting climbs on boards and spray walls from Vancouver to Christchurch, and asking that the climbers who enjoyed my sets return the favor by setting me a climb on the Sideways Wall. Incredibly, I got responses from some faraway locations like California and Switzerland!

But there were not enough goddamn climbs.

This wealth of new climbs only further stoked the flames of my desire, for I knew that no human could set enough home wall climbs to slake my thirst for novelty.

What I needed … was a machine. Enter…

Alpha-Zero.

Now that’s a cool sounding name!

Beta-Zero it is!

I decided to research ‘ML models for generating board climbs’, and found a few successful programs using Gradient-Boosting, MLPs, and LSTM models on the Moonboard. For example, developer Andrew Houghton's website has an excellent tool for generating and grading Moonboard climbs (Github here). I eventually decided on training/testing three models:

MLP (Multilayer Perceptron) - This is nearly as simple as you can get (only beaten by a single-layer perceptron). It takes in a given position and outputs what it thinks the next position will be. It’s as simple as that.

RNN (Recurrent Neural Network) - This model takes advantage of a hidden state layer, which is modified with each “forward step” (input→output). When the model is properly trained, this hidden state allows the model to “remember” the entire history of positions when choosing the next position in a sequence. This translates excellently into generating climbs (sequences of body positions).

LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) - The LSTM model uses a more complex form of state-tracking. It has a ‘forget-gate’ which explicitly ‘forgets’ some state during the forward step, while allowing some state to pass through unchanged. This architecture addresses the “vanishing gradient” problem in RNNs (inputs from step i lose “influence” over the model’s behavior exponentially with each subsequent step). I’d seen LSTM models used successfully in the aforementioned projects, so I suspected that an LSTM would be the optimal choice for Beta-Zero.

Here was the plan:

Create a simple UI to add my wall + holds with embedded features.

Add climbs, encoding them as a sequence of body positions.

Use the climbs to train my LSTM, RNN, and MLP models.

Use a ClimbGenerator wrapper-class to generate climbs from my models predictions, using each output as the next input to the model. This is a technique called auto-regressive generation, and it’s also how LLMs work.

1. Adding the wall and holds

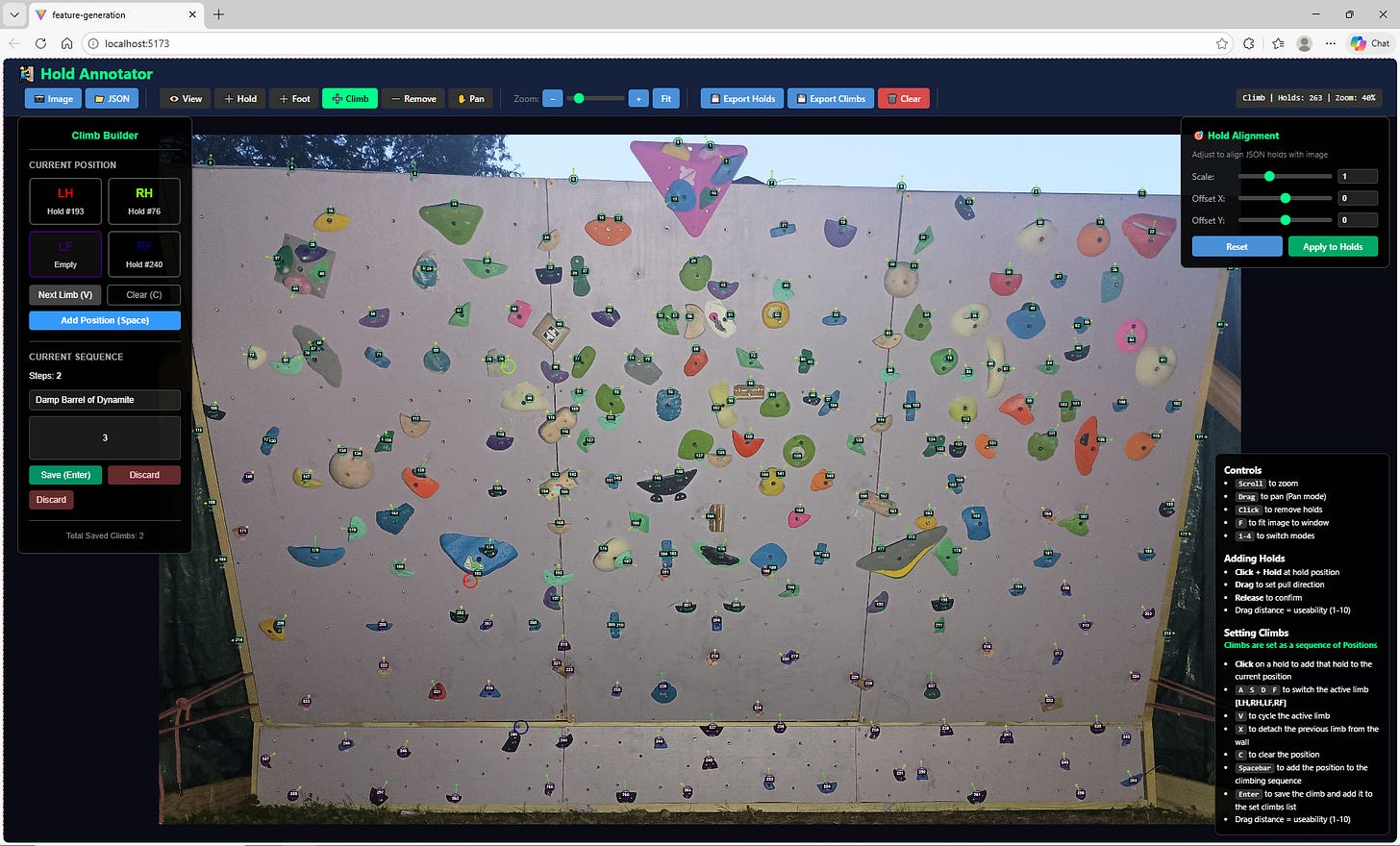

The first challenge in training a model to set climbs for my home-wall was figuring out how to encode my holds. My wall is about as custom as custom gets, with a smattering of holds across a continuous space. That means that I’d likely have to add the holds manually. With that in mind, I whipped up a data-ingestion UI (with the help of Claude Opus 4.5) which allowed me to encode my wall’s holds manually, using my homewall’s Stokt image as a coordinate background.

Each hold consisted of 6 important features which would be fed into the ML models:

norm_x, norm_y: The X and Y coordinates of the hold. (Normalized from pixel_x and pixel_y to [0,1])

pull_x, pull_y: The X and Y components of a unit vector encoding the optimal ‘pull direction’ for the hold.

useability: How easy it is to generate power from the hold. (Normalized [0,1] with 1 being an uber-jug and 0 being a splotch of paint on the wall)

is_hand: Whether or not it’s a hand-hold (1=hand,0=foot). Pretty self-explanatory.

Note that I sometimes added multiple ‘virtual holds’ to one physical hold (e.g. the grey pinch with the black thumb-catch has three ‘virtual’ holds marked on it). This is done to indicate to the model that a hold can be used in different ways, each of which might be useful in a different body position. When I was finished, I had 263 “virtual” holds.

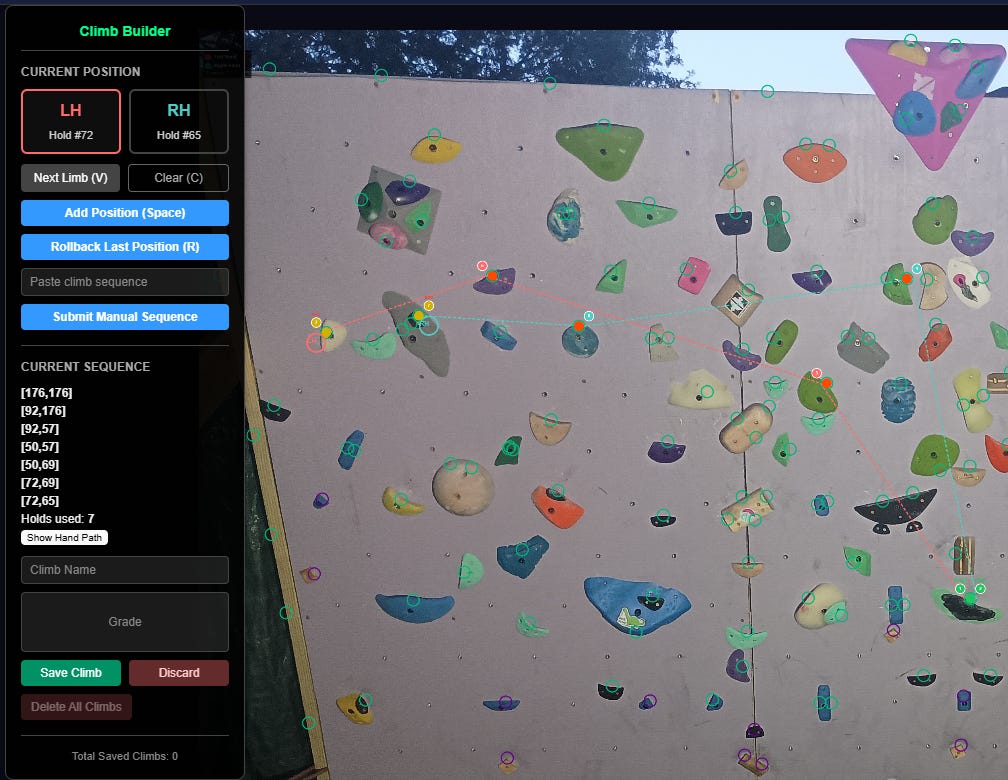

2. Setting climbs

The climb-setting UI was a lot trickier to get right. The original route-setting UI kept track of all four limbs in each position, with each limb mapped to a hold index, and -1 encoding that the limb wasn’t used. This later proved problematic for training, so I created a simpler version using hands only. Positions were added one-at-a-time to the currentClimb, which would then be saved into the ‘climbs’ state. Once I was done adding climbs, I exported ‘climbs’ into climbs.json.

3. Training the Models

The main crux of training my models was constructing a viable training dataset. My initial ‘climbs’ dataset consisted of only 30 climbs, or ~200 moves. That’s less moves than there are holds on the wall. In data science terms, this is called a ‘shit dataset’. Just kidding, it’s a sparse dataset, and wrestling with sparse datasets is what data scientists were born to do. My first trick was…

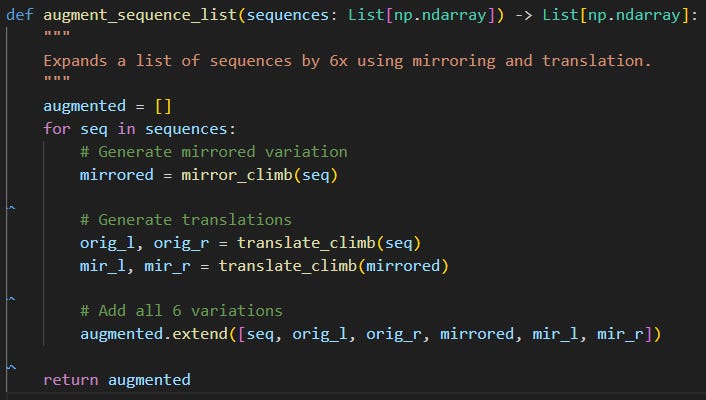

Data Augmentation

The idea of data augmentation is to increase the size of your dataset in feature space by ‘blurring’ or ‘jittering’ irrelevant data features. Essentially, you're creating data that looks ‘new’ to the model, but preserves the signal you want the model to capture. Here was my augmentation function:

Constricting the output space

Even with data augmentation, my models were not performing great. They meandered, and often generated climbs which went in circles. And the feet, which were often null (off the wall), confused the models greatly. I decided to reconfigure the +climbs UI to take hand-positions only. By shrinking the output space from 24 dimensions to 10, I made it easier for the models to pick up a signal from my data.

I also added a force_single_limb_movement setting to the ClimbGenerators, which forced them to keep at least one hand on its original hold when generating a move. And I had one last trick up my sleeve…

Movesets

Instead of adding moves as parts of individual climbs, what if I could just add every possible move from a given position at once? I could generate a ton of valid training data with relatively little manual input. Thus, the ‘moveset’ UI feature was born.

Granted, there was a big caveat with movesets: they only convey which moves are possible from a given position. They say nothing about how moves fit together into climbs. Still, my simplest model, the MLP, couldn’t make use of sequential data anyways, so I figured it wouldn’t hurt to give it some additional moves to train on.

So, what was the result of my diligent training efforts?

Training MLP: 100%|█| 5000/5000 [T_MSE=0.0131, V_MSE=0.0473]

Training RNN: 100%|█| 400/400 [T_MSE=0.0049, V_MSE=0.00]

Training LSTM: 100%|█| 5000/5000 [T_MSE=0.0021, V_MSE=0]The LSTM model prevailed! Both the LSTM model and the RNN model achieved extremely high accuracy on the full dataset after about 1,000 training epochs. But I found that the LSTM significantly outperformed RNN when it came to actually generating coherent climbs. Call it a personal preference for my personal project.

4. Climb Generation

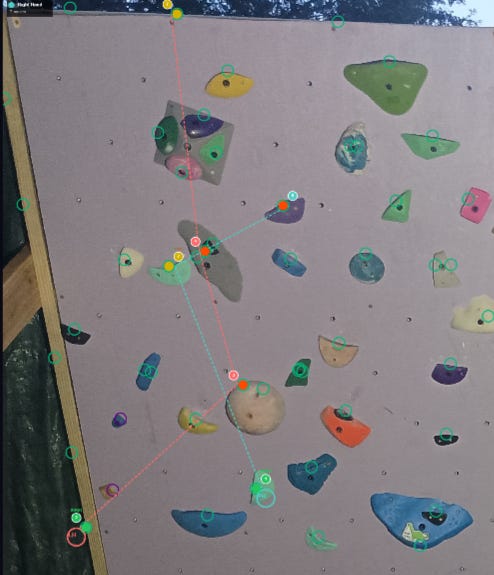

So, what could my LSTM generate? Well, here is me sending the best climb generated by the monster LSTM, which I trained for 5,000 epochs on the largest dataset I could muster (~110 climbs, ~3800 moves after augmentation).

What’s next for Beta-Zero?

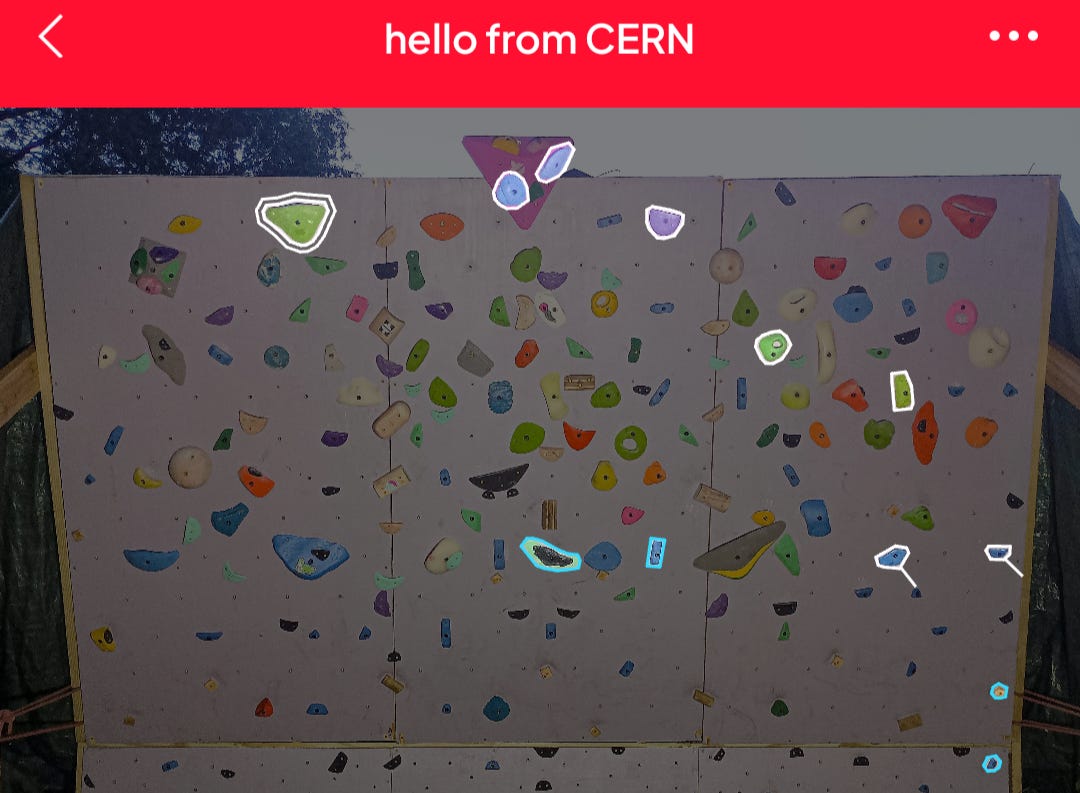

The most exciting aspect of this project is one that’s pretty easy to overlook: spatial feature-encoding of holds. It’s an obvious next step to translate my 2d spatial features into 3d, by including wall dimensions and wall angle. And a properly trained 3d model would be transferable to any spray-wall/system board in the world. All the user would have to do is input the wall dimensions and angle upon uploading it into the system.

What system, you ask?

Let’s just say that I’ve acquired more data… a lot more data. I’ve also been spending the past few weeks compiling my model-training workflow into a functional full-stack web application. You can see the current state of the project here: ML Homewall Climb Generator - Evan McCormick

Stay tuned, more updates coming soon!

Hey Evan, great read as always, it makes me so curious how Beta-Zero processes all the wall's constraints to generate novel routes, and youre really pushing the boundaries of what AI can do for niche passions!